by Amanda Ryan*

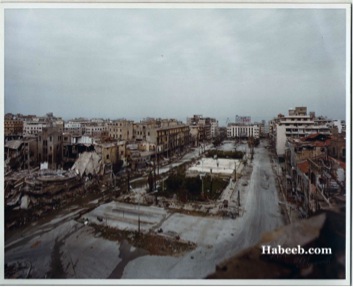

By the end of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), Beirut lay in ruins. Characterized by some as a series of individual wars,[1] the conflicts were based around a constantly shifting configuration of alliances and participants. Participants included the Lebanese military, independent militias (formed by members of the communist party, and Maronite Christian, Shi’a, and Sunni religious factions), and Israel and Syria at various points in the war.[2] The Green Line, along which some of the fiercest battles were staged, was the most severely affected zone, carving a path of destruction through the center of the city. All told, 80 percent of the buildings in central Beirut were destroyed. However, only 30 percent of those demolitions were a result of the war—the rest were carried out in the name of reconstruction and urban planning.[3] This drastic remodeling of the spaces affected by the war is emblematic of the culture of forgetting that prevailed in post-war Beirut; the takeover of public space by capital is symptomatic of the spread of neoliberal capitalism that had occurred during Lebanon’s relatively isolated war years.

A public-private partnership named Solidere[4] took control of the planning and reconstruction of the newly designated Beirut Central District (BCD). Rafic Hariri, one of the world’s wealthiest men and Lebanon’s future Prime Minister, was largely responsible for the project and owned a majority share in the company. Solidere was controversial for its expropriation of land from residents, its executives’ ethically questionable relationships with government officials, and its development of luxury properties at great profit to themselves while providing few benefits to longtime residents. The Solidere plan was approved several years after the war, after the company had already taken it upon themselves to demolish a majority of the central district, including many salvageable buildings. They aimed to produce a neatly-ordered city center, conducive to international businesses and possessing a visual unity that incorporates influences from Beirut’s ancient and modern history, from Phoenicia to French colonialism. Indicative of a desire to legitimate their design through a lineage of great empires, their slogan was, “Beirut—An Ancient City of the Future.”

The planners of Solidere drew upon elements from Beirut’s 5,000 years of history, turning the BCD into a visual pastiche of Greek, Roman, French, and Ottoman architectural styles, among others. The design and structure of the city center was particularly influenced by France, a former colonizer who is indelibly tied to the history of contemporary Lebanon. Although Lebanon had been under Ottoman rule for a significantly longer period of time, as its final colonizer, France was responsible for shaping its modern form. At the end of World War I, France and Britain divvied up control over portions of the former Ottoman Empire—the French Mandate, passed in 1920, gave France control of public assets and established exclusive trade relationships with the area that now forms modern Syria and Lebanon.[5]

France drew the boundary that separates Lebanon and Syria—though many protested that the territory should remain unified—and fostered Christian enclaves along Lebanon’s northwestern coast. France set out to make Beirut an intermediary city, which would serve as a link between the East and the West.[6] Due to the heavy damage the city had suffered during the First World War, the French undertook large-scale building and infrastructure projects. They built an international airport as well as designated districts for business and government functions, expanded the city’s ports, and re-centered the city around the Place de l’Étoile (modeled on its namesake in Paris).[7] Other buildings were constructed in a piecemeal fashion and were modeled on French architecture, without regard to the surrounding buildings. Visually, this produced a heterogeneous city with a mix of French and Ottoman architectural styles.[8] During this period, Beirut grew significantly, becoming a popular locale for cosmopolitan jet-setters and a regional hub for international business, particularly banking and trade.

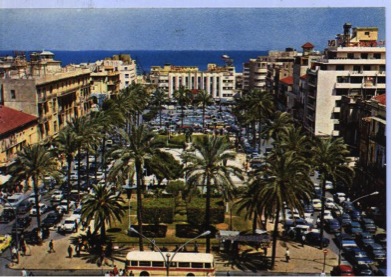

In the decades following Lebanon’s declaration independence from France in 1943 with the approval of the Allied Powers, Beirut prospered as a cultural capital of the region, earning the moniker “Paris of the Middle East.” Business relationships with the West, established during the French Mandate, produced a wealthy elite, and a bustling service and tourist economy supported a growing middle class. As a result of its growing economy, the city experienced a building boom throughout the 1950s and 60s.

Postcard of Martyr’s Square, Beirut in the 1960’s.

While architects deviated little from French Colonial styles during the 50s, the 1960s saw the “Golden Age” of modern architecture in Beirut, during which a unique Lebanese style emerged.[9] Architects during this period combined Modern architecture, under the influence of Le Corbusier, with concerns regarding local materials, craftsmanship, weather conditions, style, and function. For instance, architects put strong emphasis on terraces and centered homes around outdoor spaces to accommodate customs of socializing outside (as a result of the extreme heat). Assem Salam, one of the most influential architects of the time, is quoted as saying that they wished to renew Lebanese society and purge the cityscape of the “detritus of dead old forms,” left over from generations of shifting colonial regimes.[10]

As an imperial power, France took stewardship over Lebanon after WWI and the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire, imposing a government structure of quotas based on preserving a Christian religious majority and producing favorable conditions trade and resource extraction. A disparity in economic and political opportunities for the more “Western” or cosmopolitan Lebanese and villagers who remained more traditional created tensions within the country, which eventually led to the Civil War. In post-war Lebanon, there existed the fear that common perception in the West may cause people to dismiss the war as sectarian violence—a local conflict based in tribal and religious affiliations that is none of their business. However, this ignores the region’s colonial history, during which France reinforced these divisions through its privileging of Maronite Christians in business relationships and, to protect these ties, pushing for the establishment of a permanent legislative majority for Maronite Christians in Lebanon’s constitution. In this way, France continued to exert its influence in the post-colonial period, both directly and indirectly, through its economic ties.

Though the Solidere plan was not officially approved until 1994, plans for reconstruction began significantly earlier. After the Battle of the Hotels (1975-76), during which central Beirut suffered heavy damage, the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) commissioned a plan to restore the city and improve basic infrastructure, believing that the war was over. When fighting began again in 1978, the plan was put on permanent hold. The engineering firm OGER Liban took over the project of Beirut’s reconstruction in 1983, during a lull in the fighting. This private company, owned by future Solidere founder Rafiq Hariri, had minimal oversight from a paralyzed government and completely disregarded the 1977 plan. OGER Liban hired Dar al-Handasah to come up with a new, more “modern” plan for the BCD and began to demolish salvageable buildings in the city center under the guise of “cleaning up” war damage. This included some of the area’s most notable structures, including souk al-nourieyeh, souk sursock[11], and a large portion of the historic Saifi neighborhood. After another spike in the conflict, OGER Liban drafted an even more drastic city plan in 1986. This plan called for the destruction of 80 percent of all buildings in central Beirut, and was accompanied by another round of indiscriminate demolition.[12]

In 1991, the Taïf Agreement signaled the end of the war, and the Solidere plan— from which Beirut takes its present form—began to take shape. In 1991, former OGER Liban executive Fadel el-Shalaq was appointed to head the CDR. Under his direction, the agency pushed to consolidate reconstruction under a configuration known as a joint public-private stock company, and hired OGER Liban consultant Dar al-Handasah to draw up plans for the new city center. According to laws governing private-public real estate developments, private companies were allowed to expropriate land and develop it according to their own plans, including any necessary infrastructure. A new company would be formed, in which the government becomes a 25 percent shareholder and the private owners would hold the remaining 75 percent. For the purposes of reconstruction in central Beirut, the Soldere company was formed. After the Lebanese Civil War, the Solidere Corporation exploited this law to demolish and remake the center of Beirut according to the vision of their CEO Rafik Hariri,[13] and made a tidy profit in the process.

Photo of Martyr’s Square during the war, 1978. Photo: Gaby Bustros.

Rafiq Hariri, who was soon to be elected Lebanon’s Prime Minister, provided much of the initial capital for the project. Much like the 1986 plan, the final Solidere plan called for the demolition of 80 percent of the BCD, though many assert that only one-third of those buildings had been damaged beyond repair as a result of the war.[14] Under existing laws, Solidere expropriated land from its owners and gave them the equivalent of “market value” (according to their assessment) in Solidere shares. Property owners were given little choice in the decision, as those who opted to refurbish their own properties were subject to Solidere’s stringent regulations and approval. After redevelopment, many former residents were unable to pay the inflated housing prices and could not return to their neighborhoods.

The Solidere Plan has been the subject of much debate and criticism since its inception. The plan has been heavily criticized by residents, artists, intellectuals, and urban planners, who resented the loss of Beirut’s character as well as alleged official graft and corruption, which resulted in massive profits for the Solidere company. For some, the destruction of “old” Beirut amounted to an erasure of memories from the war. Others asserted that Solidere pursued economic interests to the detriment of the public good.

Solidere’s plan called for the rebuilding of residential blocks in unified styles, the establishment of a new economic district, landfilling 60 hectares of the waterfront for the construction of modern glass towers, and rebuilding or improving infrastructure, including streets, parks, sidewalks, and telecommunications. While efforts were made to save and restore buildings of antiquity (pre-18th century), structures built after that were generally demolished. Of the modern buildings that were saved, the majority dated from the French Colonial period, whereas the modern buildings designed by Lebanese architects in the 1950s and 60s disappeared. With the bulk of property in central Beirut demolished, the uneven redevelopment begun during the French Mandate could be completed—streets were reordered in wide boulevards that terminated in grand plazas, and housing blocks were built to uniform heights and styles, like those on Champs Elysées in Paris. This tendency negated the unique style and Lebanese identity that architects had begun to develop for their buildings in the 60s, and turned back the clock to the French Colonial period, as if independence and the Civil War had never happened.[15]

As Lebanese historian Sune Haugbolle observed, “The nostalgia embodied in the Paris of the Middle East…drew criticism from people who pointed to the amnesic gap left by missing references to the war, while some found it curious that the monuments of the old colonial power should be favored.”[16] The Solidere Corporation attempted to legitimize their project by invoking the city’s connection to great empires and appealing to citizens’ pre-war nostalgia for the more prosperous times. Written materials commissioned by Solidere also make frequent references to architectural projects in Western cities that are associated with modernity and economic strength—from Haussmannization in Paris to High Street in London. The new Beirut Trade Center is also compared to the NY Citicorp building, naming both structures symbols of “commercial prowess.”[17]

Walid Ra’ad/The Atlas Group, Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves, 2003.

Artist Walid Ra’ad alludes to the elites’ aspiration towards Western culture in a series of photos from The Atlas Group Archives, filed under Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves (2002). The photos purport to be the only existing photos of the historian Dr. Fadl Fakhouri, the “source” of a large portion of the archive. They depict Dr. Fakhouri on vacation during his “one and only trip outside of Lebanon,”[18] which, tellingly, was to Paris and Rome, the seat of colonial power and influence in Lebanon, and the birthplace of Western civilization, respectively. One after another, the photos show Dr. Fakhouri, alone, dwarfed by ancient monuments, gothic churches, sprawling landscaped parks, and neoclassical architecture. The few indoor snapshots show Fakhouri in sparsely furnished, poorly lit hotel rooms and restaurants; while he is able to visit the sites, he is not fully able to participate in the social and consumer activities of his Western peers. The photos of Dr. Fakhouri express both a desire to assimilate with and absorb the history of Europe and profound feelings of alienation and disconnection.

The work effectively captures both the experience of the exile and of the post-colonial nation. Both the colonizer and the colonized define their nationality in relation to their difference from the other—the colonizer must present a united front in order to dominate another territory while the colonized define themselves in resistance to the encroachment of a foreign nation.[19] As Walter Benjamin famously argued, history is written by the victors[20]—and the post-colonial nation has been written into Eurocentric history in terms of its relationship with its former colonizers of the West. Throughout many works produced in post-war Beirut, artists question how this history became a “fact”; they aim to find ways to define their nation through their experiences of lived events rather than the process of negation. Fakhouri’s attempt to fit himself in with these monuments to history and power, only to be dwarfed by them, is symbolic of the oppressed nation’s struggle to escape the shadow of Western history. The juxtaposition of those photos with the images of Fakhouri quite alone in social spaces reflects the exile’s attempts to assimilate with their host culture and the hazard of having one’s own identity completely subsumed by it.

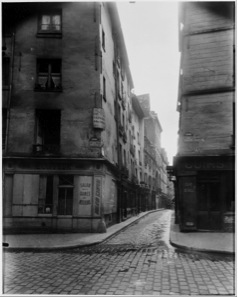

In another section of The Atlas Group Archives, the Al-Hadath archive, Ra’ad sets out on the impossible task of documenting, and thus preserving, every storefront and social landmark in the city. In the introduction to the Al-Hadath archive, explicit reference is made to the photos’ intentional reference to turn-of-the-century French photographer Eugene Atget. The photos in the archive depict the lost pockets of “old” Beirut as they were before reconstruction. Much in the same way, Atget’s photographs captured Paris’s past, focusing on the corners of the city that had escaped Haussmannization. Rather than photographing monuments or Haussmann’s wide, modern boulevards, he aimed his camera at shop windows and building details nestled on narrow, winding alleys.[21] Aesthetically, Ra’ad photos mimic Atget’s—they are taken at oblique angles, sometimes off-center, out-of-focus and devoid of human presence. This emptying of the subject produces what Deleuze would call a “pure optical situation,” or an “any-space-whatever,” in which the visual description of an image replaces narrative.[22] These pure optical signs produce an image in which fact and fiction are indiscernible—the binary between the two is unimportant in deriving its symbolic meaning. The intermixture of the real and the imaginary can lead to unexpected intersections and overlaps and produce an image with greater resonance for the viewer—as Deleuze claims, “[subjectivism] creates the real through the force of visual description.”[23]

Eugène Atget, Rue Laplace and Rue Valette, Paris, 1926

Both Atget and Ra’ad’s photos capture an element of the city that is no longer—portions of the city that have been erased by the forces of modernization and capital. In the case of Paris, Haussmann was responsible for reconfiguring Paris on a massive scale. Entire neighborhoods were razed in order to build wide boulevards and public squares. This modernization effort was initiated by Napoleon III in order to produce a city that was more governable; the wider roads prevented residents from blockading their streets and allowed the military to move through the city efficiently. The massive construction process also served to push the poor out of the center of the city and into the suburbs—once the slums in central Paris were cleared, they were replaced with monumental squares and block after block of luxury apartment buildings with regulations standardizing their heights and facades.[24] At its core, the Haussmannization of Paris bears a striking resemblance to the Solidère project in central Beirut—both projects reconfigured the class distribution in the center of the city in order to exert control over their populations and accelerate the process of modernization.

While Paris’ modernization was based on control of the city’s labor force during the industrial revolution, Solidere’s reconstruction occurred during the age of globalization, and placed its emphasis on the attraction of international capital. In Paris, Haussmannization served to protect the stability of the government and thus create an environment for domestic industry to grow. In contrast, the focus on creating an ideal environment for banking and international trade in Beirut turns the city into a way-station for international capital, which benefits the elites but does not contribute much to the general economy. In referencing Atget’s photographs with his analogous images of Beirut, Ra’ad places Solidere within the context of Haussmannization, highlighting France’s influence on Lebanon’s present, and demonstrating how history is told through its relationship to the narrative of the colonizer rather than colonized.

The Haussmannization of Paris and the reconstruction of Beirut are not discrete historical events, but rather part of a continuous progression of economic expansion from imperialism and the industrial revolution to the current state of global capitalism. In this sense, the archive in Ra’ad’s work can be considered as a place where sheets of memory intersect, as Deleuze explains is the function of the cinema screen. In Deleuze’s Cinema 2, he describes the past as existing in “sheets of time” that intersect with and exist within the present simultaneously, rather than as chronological, linear time.[25] Deleuze’s conception of non-chronological time acknowledges the ways in which the past is folded into the present through memory, false-recollection, and imagination. Likewise, Ra’ad’s work calls up the intersection between various sheets of past within Lebanon’s modern history, collapsing its colonial past with its (then) present state of reconstruction.

For many, Beirut represents the heart of Lebanon, and its rebuilding is as much symbolic as it is physical. Through the planning of Solidere, the government attempts to institute policy that rationalizes the ruins of war by covering them over with uniformly-styled buildings and gridded streets ordered for efficiency. This organization empties the streets of their life—of spontaneity and heterogeneity—to produce non-places, or non-specific spaces of communication, circulation, and consumption symptomatic of the immaterial flows of capital in the post-Fordist economy.[26] The smoothing-over of the irrational is the target of numerous artworks on the subject of Solidere, as demonstrated by the works of Walid Ra’ad.

The “disneyfied” reconstruction of central Beirut also reflects a desire to appeal to tourists and multinational business and reclaim its title as “Jewel of the Middle East.” Theorist Saree Makdisi succinctly puts it: “In view of the reconstruction project…Beirut can be seen as a laboratory for the current and future elaborations of global capitalism.”[27] Rather than being built with the needs of the local community in mind, the new construction caters to tourists, business travellers, and the ultra-wealthy of the region who are in need of a pied-a-terre. Middle and working-class residents were forced to the periphery of the city, leaving a sparsely inhabited ghost town in the center.

Walid Ra’ad/The Atlas Group, Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves, 2003.

After the Civil War, Lebanon’s populous had to cope with the economic effects of fifteen years of stagnant growth and withdrawal form the world economy. As a result of globalization, many countries went through significant structural changes during the 1970s and 80s, while Lebanon’s economy remained where it was at the beginning of the war in 1975.[28] In other parts of the world, manufacturing jobs were outsourced from the West to poorer nations and financial operations were concentrated in a handful of global financial markets. Saskia Sassen terms these hubs “Global Cities,” or cities for the management and coordination of international capital—which may include financial markets, regional headquarters, and the international real-estate market.[29]

Just as Haussmannization in Paris highlighted France’s prosperity and modern sensibilities, the planners of the Solidere project hoped that the new BCD would announce Beirut’s recovery to the world so that it could reclaim its former reputation as a cosmopolitan city. However, Baron von Haussmann’s wide boulevards, continuous facades, and manicured plazas became iconic of French urban design, while Solidere’s plans are indistinguishable from other cities. The vision for Solidere is a combination of how the West expects a “global city” to look and the West’s image of Lebanon—a pastiche of nostalgia for the resort city of the 1960s, ancient historical cities, and Orientalist flourishes. The plan elicited great controversy because it was not a plan for use by former and current residents of the city, but one conceived to cater to Western tastes and foreign capital.

The displacement of poorer residents from the city center is also symptomatic of the sentiment in post-war Lebanon that any hints of sectarianism will make the nation seem “backwards” and “anti-modern.”[30] In other words, the Solidère project served to produce a homogenous, conflict-free zone, which would demonstrate Lebanon’s ability to overcome its divisions and re-emerge as a modern city. However, sectarian divisions and wounds from the war were far from being eradicated—they were merely pushed aside, forced to remain covert. The official policy of reconciliation in Lebanon decreed that all war crimes be forgiven and public discussion of the war was discouraged. War criminals retained their posts in the government while conflicting populations were pushed out of the center of the city, so that a peaceful, harmonious image could be presented to the West. In fact, the Solidère project was an integral part of the government’s policy of public forgetting after the war—the businessman responsible for the development soon left his company’s leadership (though he retained significant financial stakes) to become Prime Minister in 1992, two years before after which the final plan was approved.

As a prominent symbolic location at the center of Beirut, Solidere forces the appearance of unity and consensus, though it only serves to exclude dissenting communities from the post-war landscape and erode the country’s reformed democratic government. The desire to produce the impression of stability to appeal to foreign investors in fact undermines the Western version of democracy that is widely upheld as the standard. Political theorist Chantal Mouffe argues that consensus is anti-democratic—in order produce an agreement, some positions are necessarily repressed.[31] Politics shifts towards centrist opinions as a matter of pragmatism and those who disagree are dismissed as “radicals.” Democracy requires that citizens are able to voice their opinions and have them heard; consensus tends towards authoritarianism—politicians do not speak for the morals of their constituents, but function as bureaucrats carrying out a task.

Walid Ra’ad/The Atlas Group, Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves, 2003.

In the case of the Solidere project, it was executed in a decidedly non-democratic manner. Demolition began during the war with no plan approved, property owners were discouraged from rehabilitating their own properties (they were bought out instead), and the chief shareholder in the company, Rafik Hariri, became Prime Minister while the plans were being drafted. Despite a town hall meeting in which residents voiced strong concerns about the project, the final plan changed little; the public good was subverted in order to enrich the private investments of Hariri and his associates.

Beiruti artists almost uniformly incorporated Beirut’s reconstruction into their works in the decade after the war in order to challenge dominant representations within the landscape of late capitalism. Just as war criminals were forgiven and any discussion of the war discouraged, an opaque process awarded control of the vision for the BCD to the first company to propose a plan, all under pretenses of pragmatism and reconciliation. After fifteen years of war, the desire to return to normalcy superseded the democratic process. In order to prevent the tyranny of consensus, Mouffe makes the case for radical or agonistic democracy, in which citizens adopt a multiplicity of subject positions and engage in activism and debate in the name of the common good.[32] Through their works, these artists attempt to disturb the complacency of consensus and encourage an active debate, or at the very least, reflection, on the government’s post-war policies. They achieve this through questioning the facticity of the archive and producing new cultural spaces where their positions can be made visible.

—

[1] As noted by eds. Hlavajova and Winder, some prefer to refer to the Lebanese Civil War in the plural in order to signal the multiple conflicts, occupations, and adversaries involved throughout the 15 year period from 1975-1990. Maria Hlavajova and Jill Winder, “In Place of a Foreword: A Conversation with Rabih Mroué” in Rabih Mroué: A Bak Reader in Artists’ Critical Practice (Rotterdam: BAK, 2012), 15.

[2] Though many of the militias were formed around religious affiliations some would hesitate to call it a religious war. Militias adhering to the same religious denomination were not necessarily unified and were at times adversaries. Political beliefs, power struggles, and economic inequality should be considered equally important.

[3]Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere.” Critical Inquiry 23, No. 3 (Spring, 1997): 670-4.

[4] An acronym for the French phrase that roughly translates to “The Lebanese Company for the Development and Reconstruction of Beirut” (full French phrase not mentioned in any sources).

[5] Fawwaz Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon (London: Pluto, 2007), 80.

[6] Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon, 91.

[7] Place de l’Étoile, now known as Place Charles de Gaulle, is a square located in the center of the city where twelve avenues converge; it may also be recognized as the location of the Arc de Triomphe.

[8] Assem Salam, “The Role of the Government in Shaping the Built Environment”, in Projecting Beirut: Episodes in the Construction and Reconstruction of a Modern City, eds. Peter G. Rowe and Hashim Sarkis (Munich: Prestel, 1998), 122-3.

[9] Jed Tabet, “From Colonial Style to Regional Revivalism: modern architecture in Lebanon and the problem of cultural identity,” in Projecting Beirut, eds. Rowe and Sarkis, 93-96.

[10] Ibid, 96.

[11] Two of Beirut’s historic open-air marketplaces.

[12] For a more in-depth discussion of the development of reconstruction efforts throughout the war, see Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere.” Critical Inquiry 23, No. 3 (Spring, 1997): 660-705; and Tamam Mango, “Solidere: The Battle for Beirut’s Central District” (MA Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004).

[13] It has been suggested that Hariri’s idealized memories of the city from his youth (he left Lebanon and made his fortune is Saudi Arabia during the war) inspired Hariri’s vision for reconstruction, which held great sway over the final plan; Richard Becherer, “A matter of life and debt: the untold costs of Rafiq Hariri’s New Beirut,” in The Journal of Architecture 10:1 (2005): 1-42.

[14] Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut,” 670-4.

[15] Farès el-Dahdah, “On Solidere’s Motto, ‘Beirut, Ancient City of the Future,” in Projecting Beirut, 73-76.

[16] Sune Haugbolle, War and Memory in Lebanon, 85-86.

[17] Angus Gavin, Beirut Reborn, 40.

[18] Walid Ra’ad, Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves, in The Fakhouri File, The Atlas Group Archives (online, 2002).

[19] Edward Said, “Reflections on Exile,” in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 173; Etienne Balibar, “The Borders of Europe,” in Cosmopolitics, 221-3.

[20] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Concept of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, (New York: Schocken Books: 1968).

[21] Gilberto Perez, “Atget’s Stillness,” The Hudson Review, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Summer 1983): 334.

[22]Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2. (Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1985), 5-9.

[23] Ibid, 12.

[24] David P. Jordan, “Baron Haussmann and Modern Paris,” The American Scholar, Vol. 61, No. 1 (Winter, 1992): 99-106.

[25] Deleuze, Cinema 2, 116.

[26] Marc Augé, Non-Places, (London, New York: Verso, 2008), VIII.

[27] Saree Makdisi, “Beirut/Beirut,” in Tamáss, ed. David, 36.

[28] Toufic Gaspard, “Economic Performance in a Monetary Crisis Environment: the gross domestic product of Lebanon in 1987,” in Reconstruire Beyrouth, (Lyon: Maison de l’Orient Méditerranéen, 1991), 271-286.

[29] Saskia Sassen, The Global City, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[30] Haugbolle, War and Memory in Lebanon, 22.

[31] Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political, (London: Verso, 1993).

[32] Ibid., 30-34.

*Amanda Ryan is a recent graduate from the MA in Modern Art: Critical and Curatorial Studies program at Columbia University.

You must be logged in to post a comment.